Introduction

The Fool

The fool archetype is prevalent in literature, mythology, and folklore across diverse cultures. This character is often portrayed as a jester, clown, or trickster who engages in foolish or comedic behaviour. While the fool's purpose is to provide entertainment, he often employs satire and humour to critique authority figures, societal norms, or ambitious individuals who seek prominence and power.

In Europe, during the Middle Ages, the fool was the court jester. He was free to ignore the established order and speak unpalatable truths that could be interpreted as treacherous or disloyal. Because he was a fool and regarded as a plaything of the king, the Jester was not censured for his audacity. Instead, like Shakespeare’s fool in King Lear, he was considered useful in shielding the king from hubris, while revealing the real intentions of the courtiers and noblemen.

A present-day incarnation of the court Jester is the professional comedian who lampoons the idiosyncrasies of society without fear of being censured or cancelled. Both the court jester and the comedian are gifted with scathing insight into the motives and behaviours of others and, in some way, represent the unconscious voice of a culture.

Then, there is also the wise fool—a naïve outsider who lacks the cynicism of the jester. Like Socrates, the wise fool knows he knows nothing and goes in search of knowledge and truth. He is the persistent fool of Cervantes and Blake, who gains wisdom through experience.

In Renaissance Italy, the wise fool was depicted as a barefooted, ragged figure in a set of 15th-century playing cards. These playing cards were modified and redesigned, as their popularity increased over the course of generations. By the 20th century, the once impoverished fool in the card game had undergone a transformation into a well-dressed individual, carrying a small bundle of possessions over the shoulder and setting forth on a journey of discovery. Through this gradual metamorphosis, the marginalized outcast emerged as the central character in Tarot cards, embodying the pursuit of wisdom in the postmodern world.

The Tarot fool serves as the protagonist of this story.

The Tarot

The evolution of the Tarot, from an Italian Renaissance game of cards to a New Age Philosophy, reveals much about the development and dissemination of mythologies.

The elegantly named Visconti Sforza deck is the earliest known set of Tarot (or Tarocco) cards. Commissioned by the Duke of Milan in 1441, these intricately hand-painted cards were initially used for a game resembling Bridge. The refinement of the Visconti Sforza deck suggests a potential existence of the Tarot game before the 15th century, but the exact origins have faded into obscurity.

Tarot might have remained an exclusive pastime for the Italian nobility, if not for a seismic event that transformed European culture — the invention of the printing press. As the Tarot spread to France and Switzerland, much of its design underwent modification. By the 17th century, the Tarot de Marseille, printed from woodcuts, emerged as the standard deck for Tarot games. In contrast to the opulence of the Visconti Sforza deck, the simplified imagery of the Tarot de Marseille conveyed the severity and magical realism of feudal society.

This magical realism captured the imagination of Antoine Court de Gébelin, a French etymologist, author, and freemason. In a 1773 publication, he posited that Tarot cards held secret knowledge. Despite the absence of historical evidence, de Gébelin asserted that Egyptian priests had distilled the ancient Book of Thoth into Tarot cards, with the intention of preserving arcane knowledge.

Subsequently, a French magician, Jean Baptiste Alliette entered the scene. He authored a book on the meanings of the Tarot and also designed his own Tarot deck, known as the "Grand Etteilla." Alliette claimed that the Egyptians originally used these cards for fortune-telling. Intriguingly, Alliette made a living from the myth he had fabricated and established the notion that Tarot cards could reveal the future.

In the 19th century, a fascination with divination and occult phenomena became deeply ingrained in French heterodoxy. Aspiring mystics found that the tableau rasa of the Tarot readily accommodated their speculations. Eliphas Levi (1810-1875), a French esotericist renowned for his popular books on magic and occultism, promoted the idea that the Tarot constituted a system of esoteric symbolism, harbouring concealed secrets related to the Qabalah, numerology, astrology, and alchemy.

Levi's theories garnered the interest of A.E. Waite, an English writer, Freemason, Rosicrucian, and member of The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn— occult societies dedicated to exploring Hermeticism and metaphysics.

Animated by Levi's ideas, Waite joined forces with fellow Golden Dawn member Pamela Colman Smith. Together, they embarked on a collaborative endeavour to create a unique Tarot deck that would encapsulate the esoteric principles advocated by these secret societies.

Inspired by the Sola Busca Tarot (1493) known for its detailed illustrations of all 78 cards, Colman Smith made timeless and universally evocative images that softened the ominous atmosphere usually associated with the traditional Tarot de Marseille.

Waite penned the companion volume, the Pictorial Key to the Tarot, providing a guide to interpreting the cards. After the deck was published in 1909 as the Rider-Waite Tarot, (with “Rider” being the publisher’s name), the Tarot came of age and became a worldwide phenomenon.

The Rider-Waite Tarot remains the most widely used deck today.

Perspective

The contemporary Tarot arrived during the cultural upheaval that characterized the formative years of the 20th century. As the psychologies of Freud and Jung, the literary innovations of Joyce and Eliot, and the emergence of modern art movements, expanded the horizons of the inquisitive mind, literature on the Tarot, exploring its history, interpretation, symbolism, and practical applications, was published and continues to be expanded upon.

Numerous authors believed that the Tarot comprises archetypal images and universal themes, presenting a narrative structure symbolizing stages of spiritual development through its sequence of cards. Though interpretations vary widely, certain concepts have become established in spiritual and New Age practices.

Although the Tarot was incubated in the realms of pseudoscience and confirmation bias, its attraction lies primarily in the imagery of the cards, which has an inimitable effect on the human imagination. For some, the Tarot serves as a tool for spiritual growth, self-discovery, and divination, while others perceive it as a form of entertainment or psychological reflection.

The Major Arcana

As an art student, in the 1970’s, I first came across Tarot cards. I was impressed by how unusual they were and was immediately curious about their origin and meaning. The proposition that Tarot cards might reveal the future was appealing, especially to my credulous mind, but my attention was ultimately captivated by another feature of the cards - the idea that a group of these images mapped out an archetypal journey through life: The Fool’s journey.

A Tarot deck consists of 78 cards, which are split into two groups, the Major Arcana and Minor Arcana. The Fool's Journey is associated with the Major Arcana - a numbered set of 22 cards that depict the influences and dynamics the Fool will encounter on the path to enlightenment. As the Fool progresses through the Major Arcana cards, each card represents a different stage or aspect of his life’s journey, with its challenges, lessons, and opportunities for growth. I was familiar with cultural rites of passage, where ceremonies mark an individual's transition from one stage of life to another, such as birth, puberty, marriage, and death. However, the Fool’s Journey suggested an ancient, deeper, and multifaceted understanding of life.

A decade after leaving art school I made a series of twenty-two small paintings on the theme of the Major Arcana. It was a tableau of my journey as a young artist. I combined portraits of friends and acquaintances, who personified the characteristics of individual cards, with imagery from the history of art and significant events of the 20th century. The paintings were exhibited in Dublin and acquired by a private collection.

Afterward, my work as a painter led me into other areas of life, and I gradually forgot about the Tarot.

The Wounded Fool

Some years later, in 2004, my Major Arcana paintings were again on exhibition. This time at the Hunt Museum in Limerick in conjunction with a Symposium on Symbolism in Art. One of the speakers at the symposium was Mark Patrick Hederman, a Benedictine monk, philosopher, and writer whose book “Tarot, Talisman or Taboo?” had recently been published. Hederman regarded the Tarot “as unique manifestations of a deep, almost inaccessible part of ourselves which is essential for us to access if we are to come to terms with the world, we have created for ourselves to live in. These cards are a moving (in both senses of the word) kaleidoscope, a symbolic map of the penultimate layer of humanity. The only other access to this landscape we have, apart from our dreams, over which we have little control, is through the mediumship of artists.”

In addition to an absorbing presentation of the Tarot, Hederman’s book, which bears the influences of Jungian Psychology and Christian Hermeticism, contains a series of meditations on each of the 22 Major Arcana cards.

After attending the symposium and reading Hederman’s book, my interest in the Tarot was gradually renewed as I occasionally found myself drawn to the "Metaphysical," "New Age," or "Spiritual" sections of bookshops where I could check out new books on the Tarot.

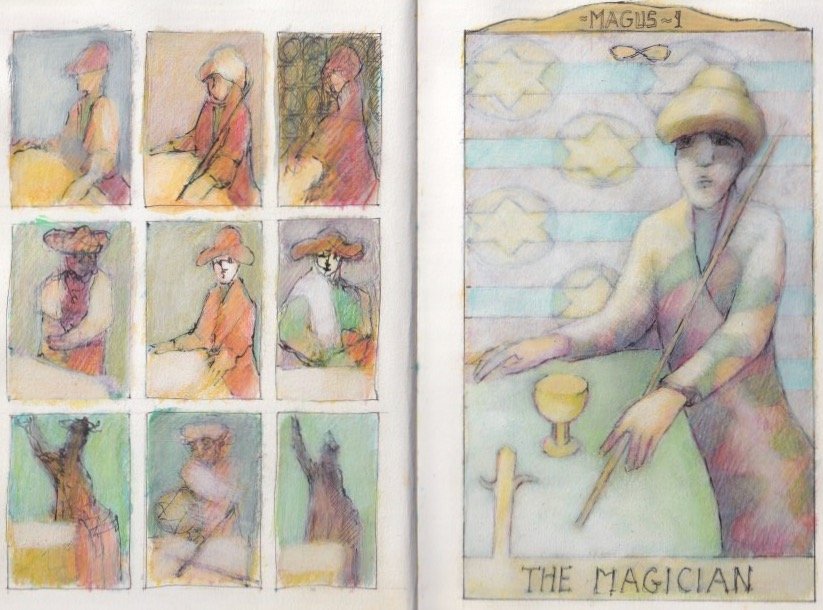

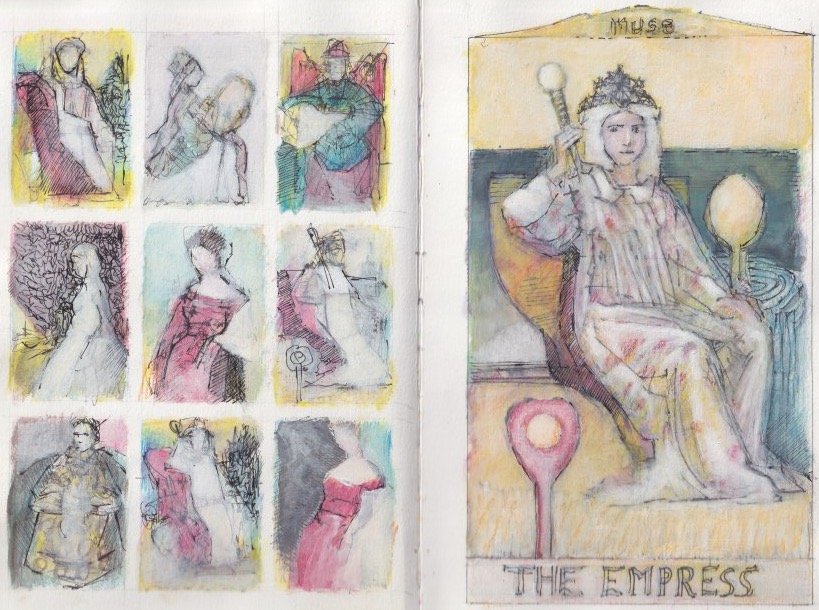

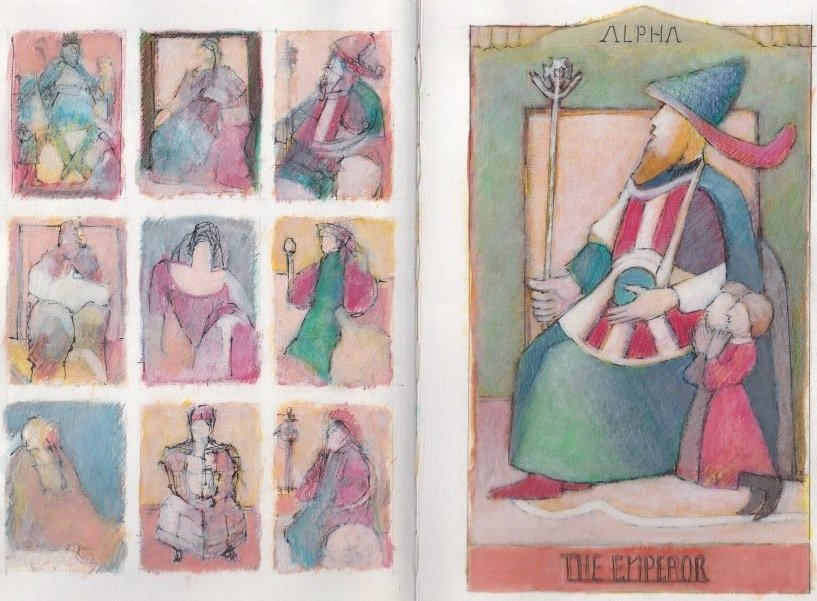

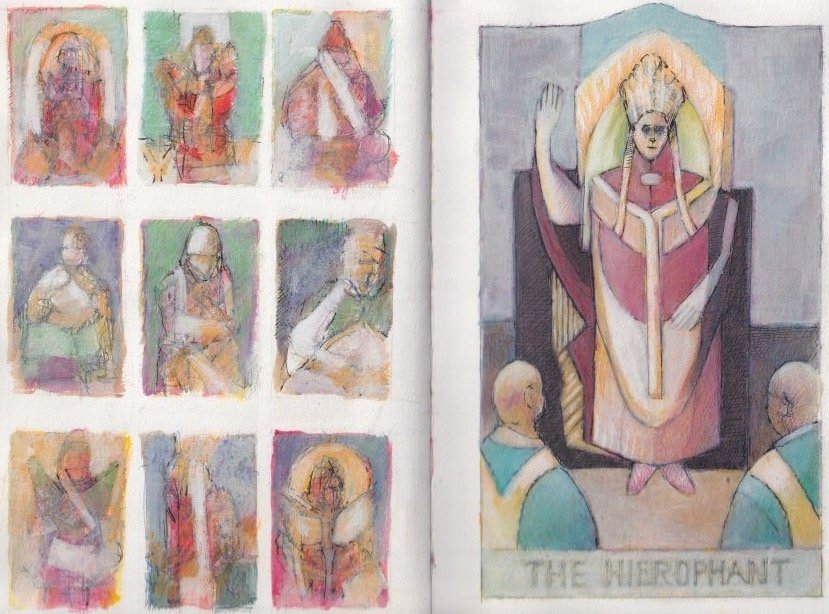

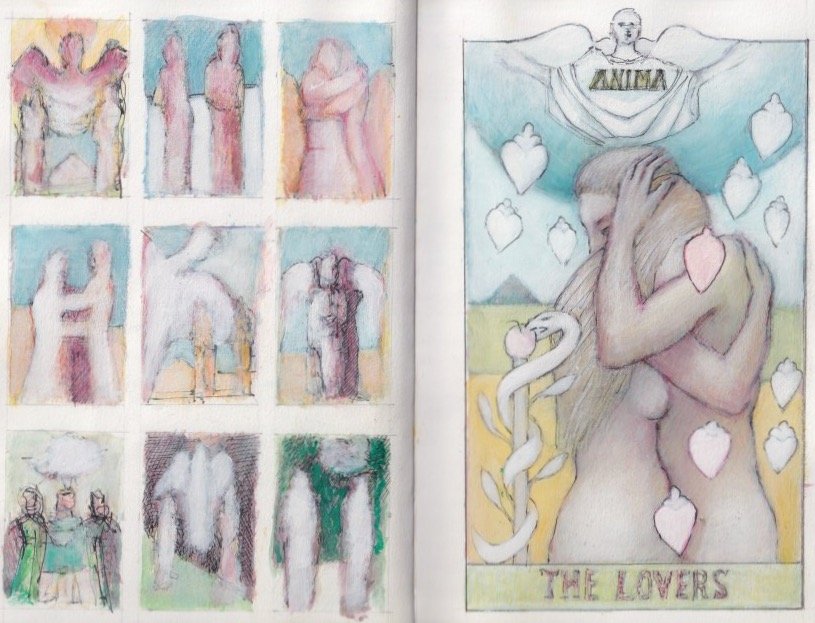

An artist’s work is sometimes cyclical, where former themes are revisited in the light of experience – sometimes decades later. In 2016, thirty years after making the Major Arcana paintings, I began tentative studies of the Major Arcana images in an artist’s notebook, using watercolour pencils and gesso.

I like to combine drawing and writing in artists’ notebooks, as a dialogue between both mediums often occurs. Eventually, a series of images and accompanying ideas about the Major Arcana took shape, while I considered the nature of the Fool’s Journey in the 21st century.

The Fool can no longer be the innocent adventurer of the Rider Waite Tarot, cheerfully setting out to explore a virgin world. Instead, the modern Fool is a microcosm of the world he inhabits. The world that lost its innocence with the bombed-out cities and ethnic cleansing of World War II, has become a narcissistic and addicted world of growing inequality, nuclear proliferation, environmental destruction, and climate change. The Fool is now a psychically wounded individual who sets out to distance himself from the trauma of his personal history, and somehow achieve the “miraculous” state of consciousness he had glimpsed during a psychotic episode.

The Fool is, ultimately, postmodern man in search of his soul, and this is his story.

Excerpt from The Wounded Fool comprising of the first six cards from the Major Arcana.

0. The Fool

It is the Fool’s destiny to go in search of himself. An adventure he undertakes with the naïvety of one who carries a wound that is older than memory.

The thin skinned Fool is saturated with the mystery of life. His misfortune lies in being too tuned into the inner life of others. He feels the frequencies of their insecurities and witnesses the drift of shadows behind their masks. At any given moment he suffers a quiet restlessness, in which he craves approval while being disturbed by the real and imagined judgements of those who are infringed by his perceptions.

To manage his unease the Fool retreats into the miasma of imagination where his distracted instincts are endlessly waylaid. He opens the doors of desire as though they were the gates to freedom. He splits from his spirit and lives in his head, exiled from the ripening moment of the heart. Already abandoned, the Fool abandons himself and becomes an outsider – a special reject in search of an elixir that gratifies the ego and eradicates the angst. With medicated instincts he navigates as a people pleaser, a tourist without a map; all the while suspecting that some secret of survival, some order of competence, lies beyond his grasp.

In his self-reliance the Fool flounders like an ordinary god, bereft of the power to create, and slides further into self-sabotage where a latent death wish worms his core. He fails to tame stray voices in his head. Human contact makes him nervous, certainties recede and an accelerating paranoia sharpens his shame and provokes his defiance. He seeks a seclusion he previously avoided, only to encounter a shocking isolation where menace stirs the air and a recurring dream, in which the Fool murders the one with the last wish, agitates his mornings.

The streets taper with danger and around each corner a spectre awaits. He flees the city and seeks refuge by the ocean. On the cliff of extinction he edges towards oblivion, tempting the bitter wind and the blackened rocks of a violent sea. Suddenly he breaks like a traumatized soldier breaks in the trenches and his frenzied prayer flaps into the ether.

In this capitulation his identity is discarded like a useless rag and he is momentarily released from all delusions of importance. Instantly he is a nerve end of God, a minuscule element of consciousness encountering the anima in the jungle of the id. The Fool glimpses the miraculous in the yearning energy of trees and the symphony of sunsets. In that instant of clarity he grasps that reality can only be exactly as it is – that it is not his to alter, but only to accept.

Like a returning salmon, the Fool’s ultimate destination is the source, the fountain of enlightenment, the higher Self. He consults the psychologists and searches the libraries for the secrets of sanity or, at least, a blueprint of the maze. But, for the Fool, the formulas of others are as elegant and useless as the opening moves in a familiar game of chess. It occurs to him that he must follow the curve of his growing curiosity and abandon himself to whatever experiences an alternative life might place in his path.

For this adventure the Fool chooses the guise of a vagabond - the antithesis of the peasant and the bourgeoisie. As an outsider, he may overcome the conditioning of his culture and gain distance from his past.

Then, in the way a luck-struck gambler trusts the roll of a dice, the Fool decides to trust the universe and brings his newfound quest to the alter of chance.

1. The Magician

At the table is the Magician, an illusionist who shunts the levers of perception and side-lines the rational, making the invisible visible.

With mesmerizing movements, he flourishes the signs, symbols, and signifiers of desire; wands for power, swords for truth, cups for emotion, and pentacles for possession. In a performance that presents his followers with absolutes they had never dared imagine, the Magician awakens the quiescent dreams of his audience as visions in the glimmering air. Air he breathes as though it were the breath of God.

Among the Fool’s delusions is a Messiah complex, a fantasy where he heals the multitudes, evangelizes from the rock of ages, and basks in the adoration of his flock. He instantly discerns, in the Magician’s craft, the possibility of performing miracles, or at least the appearance of miracles. In the dejavu of self-fulfilling certainty, the Fool decides that his life’s purpose is to be a master of illusion and that the Magician is the person he must become.

To this end, the Fool ingratiates himself with the Magician. He acquires a wand, a hat, a rabbit, and a dove and through endless hours of practice, he disappears and resurrects the bewildered animals from the ether. He mimics the Magician’s manner, accent, and affectations. As his determination and sycophancy gain his mentor’s attention the Fool’s delusions inflate. He begins to regard himself as an exceptional apprentice, a chosen one among the Magician’s disciples. In this first flush of success, it becomes imperative, for the Fool, that the world acknowledges his uniqueness – a uniqueness that would be evident in a superior staging of a sorcerer’s trick.

He beseeches the Magician to share a dazzling secret of the clandestine craft only to be told to make haste slowly, not to want too much too soon and that what is his will come to him. Because the apprenticeship requires total command of the moment, his mentor explains, a long and repetitive road lies before a student Magician. Magic is an art form that takes years of dedication and discipline to master.

But such patience and perseverance lie beyond the frontiers of the Fool’s determination and he mistakenly assumes his raw aptitude will suffice. Impetuously, he repackages some tried and trusted tricks and proclaims himself to be a magician. He summons an audience and arranges the new-fangled apparatus of his alchemy upon the table with the carnival confidence of a three-card trickster.

His act is received with the faint applause of spectators who have seen too many rabbits pulled out of hats. Their feeble rattle of appreciation frustrates the Fool who has anticipated an enthralled response like the Magician’s performance invariably commands. In desperation he tries harder, only to generate unrest as his incompetence becomes painfully apparent. Eventually, the waning enthusiasm of the spectators saps his confidence. Faced with a panic attack, the Fool curtails his routine and retreats from the stage.

With the humiliating hindsight of defeat, it eventually occurs to the Fool that the Magician disregards the highways of ambition or the podiums of validation. Behind the dexterity and deception, the Magician’s mind is still rather than active, is aware without concentration, and is at ease rather than at work. Such seemingly effortless attention enables an artifice where everything and nothing fades or finds form. An integrity is involved, which the Fool cannot fathom, and a genius, which he does not possess

Such virtuosity, the Magician explains, cannot be induced; it is only arrived at through long engagement with the process from which artistry is shaped. Begin again at the birth canal, the Magician tells the disenchanted Fool, locate the source of creativity, and seek the clarity of the High Priestess.

2. The High Priestess

The High Priestess sits between pillars of initiation and reversal. Before her is the book of wisdom. Behind her is the unfathomable. Her mind is attuned to the oceanic impulse of creation, to the intention and source of her origins. Out of stillness and emptiness, her wisdom emerges as inspiration; inspiration she processes through reflection and renders into words.

In the emerging world, her visions are revered in the Temple of Solomon and at the Oracle of Delphi. Although he consults her about the future or the past, the aspiring man is often unmasked by her insight and torn by her veracity. Later she appears as Mary Magdalen, an inconvenient mystic whom the church fathers rebrand as a whore, while they institutionalize the spiritual. On the veneer of history, her provenance fades; but her presence remains on the side altar of the human psyche.

Masculine reasoning cannot map the labyrinth of the High Priestess’s awareness - a sanctum that is resistant to the mythologies of theologians or the proclamations of philosophers. Yet the pathways to her wisdom are hidden in full view: in fossils of coincidence, in patterns and dreams that are discernible only with distance and memory, in the subtle mind of the heart when the gross mind of the senses quietens and self-obsession withers on the vine of silence.

Within her contemplations, the drifts of destiny are revealed like whispers. She sees the cunning of displaced animals, long forced to ground from mother trees, who find fulfillment in human enslavement and limitless greed. She watches the empires inflate and degenerate like white dwarfs. She observes the seeds of callous futures take root in the neuropathways of corporations, while she examines the sinister shadows of a synthetic world stretched across her temple floor.

From this penumbra, she reads the fortune of the male endeavour as it proudly sails its titanic ambitions into the icefields of consequence - an Armageddon which may only be averted through the female principle.

The Fool, meanwhile, is animated at the prospect of acquiring clarity and he approaches the High Priestess with the zealous expectation of a pilgrim witnessing an apparition. For as long as he can remember, the Fool’s mind has been a circus of confusion. It is as though his thinking and intuition have been at odds with each other; resulting always in a cocktail of emotion and an inability to appraise any situation.

In preparation for enlightenment, the Fool sits in the lotus position and discovers, despite his determination to be an outstanding meditator, that his mind is disturbed rather than serene. Each thought that arises mushrooms darkly into a scenario of impending disaster, or morphs into a re-enactment of some past humiliation. Soon he is besieged by memories he would rather forget and dire prospects he scrambles to avoid.

Undaunted, he persists and meditates morning, noon and night at the shrine of the High Priestess. But instead of basking in her venerable presence, the Fool continues to sink into the swamp of his history and shiver in the fearsome winds of anticipation. His attempts to harvest intuition lead to superstition instead of insight and his nervous system is overcome with apprehension.

Worst of all, the High Priestess regards him with indifference.

What began in hope, ends in failure as the Fool retreats from the torture chamber of his thoughts and abandons the hill of silence.

“Why can I not find enlightenment?” He demands of the High Priestess.

“You cannot be still,” the High Priestess informs the discouraged Fool. “Your natural rhythms are laced with trauma. Your anxiety floods the silence.”

“What can I do?” The Fool pleads, “I cannot continue like this!”

“To heal yourself, it is vital to secure the nurturing power of the world. Seek out the Empress.”

3. The Empress

The Empress sits in her garden – a paradise where the spiritual manifests as the physical. She generates the potent Spring where all is formed or stillborn, nurtured or neglected. Birth, sex, and beauty are her dominion and, in this fundamental expression of being, the Empress reciprocates life’s longing for itself.

Throughout antiquity, she is a goddess with numerous titles. To the Athenians she is Aphrodite, an enticer of gods and mortals; to the Romans she is Venus, the mother of good fortune and fertility and the source of love, pleasure, and passion. She bequeaths creativity and resilience to the human enterprise and fosters the empathy and sensuality that sustains the individual. For the classical sculptor, she is the muse who incorporates the inner and outer splendour of the world, and whose marble presence holds the poetry of the body and the eternity of the soul. Later, in the Renaissance, the Empress is idealized as the nurturing mother who manifests nature’s abundance, beauty, and fertility.

Because she carries the life and first influences the child, the Empress supersedes the male. In her gift is the bond between mother and child, the meadow of belonging or the desert of isolation, the attachment or the void.

In the way a leaf absorbs sunlight and a bee is drawn to a flower, the passions of the Fool are inflamed by the Empresses’s perfection. Her magnetism sheens with its promise of happiness. Euphoric now, with anticipation, the Fool crosses the garden to where the goddess sits upon her throne.

He arrives with his begging bowl of attachment and bares his woken anima before the Empress of his desire. Like a courting jungle bird, the Fool discards his inhibitions and squawks in anticipation of her touch; a touch that can unblock the sacral chakra of his bliss.

But in place of fulfilment, a nervous energy agitates the air.

In a quicksilver moment, the power of love becomes the love of power. The Empress’s face turns stern as an inquisition, and her eyes are assassins. She has become the Shadow of femininity. Her concern is supremacy. She is the emasculating woman who gives and withholds, alternating dutiful care with arbitrary rage; the resenting partner who withdraws support at decisive moments; the toxic parent who breaks the child’s boundaries and shames the soul.

The Fool is shattered by her rejection. His brief ecstasy shrivels to despair and his heart blackens in anger at the destruction of his dreams. He becomes too withdrawn to speak. All that remains is the bittersweet poison of unrequited love and the humiliation of loss.

With a click of her fingers the Shadow disappears, and now a maternal Empress sits on her throne observing him with the loving kindness of a mother who truly knows the nature of her child. She radiates like a Raphael Madonna and the Fool is overwhelmed by sensations of love, trust, safety, and support that he'd never known before.

“Your shapeshifting is too much for me,” the Fool protests. “I am seasick with confusion.”

“What you seek in me is the reflection of your first relationship,” the Empress explains.

“You will unconsciously recreate that relationship in your life. If it was a nurturing bond you will attract a loving partner. If it was a warped attachment, you will seek a counterfeit intimacy and lose yourself in the charm and chaos of others.”

“What you say is disturbing,” the Fool protests. “What am I to do?”

“The crucial relationship in your life is the one you have with yourself - the one you learned from your parents. Unless you accept their humanity, you will never forgive yourself.” The Empress answers. “If you have a bewildering mother, you need an astute father. Visit the Emperor.”

4. The Emperor

Within his fortress, encircled by symbols of authority, the Emperor reclines upon his throne and regards his subjects with the equilibrium of an alpha baboon surveying his harem. Implacable gatekeepers, sycophantic courtiers, battle-hardened generals, social climbers, deceitful petitioners, and scheming pretenders tread cautiously in his regal presence. The pecking order of this menagerie, separate from the feminine sphere and its cycle of birth and death, fortifies the structured world of masculine rule and its objectives of permanence and conformity.

During his Capricornian ascent to the pinnacle of power, the Emperor discards his common identity, mythologizes his past, and sequesters an iconic name to copper-fasten his supremacy. He secures his kingdoms with an iron heart and a propensity for relentless attrition.

Order is preserved by his dark charisma – a synthesis of benevolence, scathing humour, and random violence. His authority conveys a mercurial indifference, which is reminiscent of how the waves of history are careless of human concerns or forest fires are oblivious to the survival of trees.

The Fool enters the Emperor’s domain as a supplicant in search of an opportunity to fortify his masculinity and elevate his status. Because he is new to the court and carries an air of individuality, the Fool is met with curiosity as to how he may be useful for the schemes of others. The gates of ambition are open, and he surfs the stratum of influence which moves him closer to the throne.

Since infanthood, the Fool’s instincts are misaligned with the territorial schema of his gender. No parent imprinted an imperative of self-preservation on his psyche; nor has a mentor defined the mechanics of opportunity or illuminated the loyalties and duplicities that permeate the human enterprise. Instead, the Fool oscillates between meekness and hostility, only to become a convenient target in troubled times. He meanders like a discontented animal who fails to find his place within the pack or distinguish between the minted and impoverished tracks that map the migrations of the fraternity.

Also, the Fool has a serious flaw: he cannot discern the ranks of patriarchy. Following his defeat in the Oedipal struggle, a latent hostility towards his father is transferred onto authority figures. This juvenile defiance has left him with an automatic contempt for conventional ideas and customs that are not immediately gratifying.

Inevitably, the bureaucratic character of the court irritates the Fool. In a mindless act of disrespect, he feigns indifference towards the Emperor and makes no acknowledgment of the ascendency. Instead, the Fool focuses his attention and flattery on the courtiers who surround the throne and addresses them as though their standing is equal to the Imperial power they serve. But the Fool’s words fizzle in the ether and the court is muted by a volatile glint in the Emperor’s gaze.

Instantly the Fool regrets his audacity, which has placed him in great danger. A realignment in the sovereign mind can spark a lethal shift from the stability of protocol into the slaughterhouse of paranoia. The Imperial presence can uplift or destroy. The Fool senses the fury that forged the empire and he understands, too late, that behind its ceremonial veneer, the court lives in caution of the Emperor’s vexation – a vexation which may cost him dearly.

In deathly silence, The Emperor considers the situation and finally laughs aloud at the quaking Fool who stands before him. Immediately the court erupts in hilarity.

“Only a Fool would risk the sovereign displeasure.” The Emperor announces. “We already have a jester in this court and have no use for another clown, especially one so arrogant. It is not influence or wealth you need to acquire, but the humility of a penitent. Go, seek the Hierophant.”

5. The Hierophant

Here is the Hierophant, the conductor of ceremonies from the naming to the grave. Inevitably a man, and frequently emasculated by holiness and an aversion towards intimacy.

This shaman-priest is a consequence of ephemerality and the human need for meaning. Communities conceive him to shepherd their souls along rugged paths to promised lands. Whether he is extracting human hearts upon an Aztec pyramid or banishing devils from a frenzied congregation, he lays claim to the bridge between Heaven and Earth. From this mythical overpass, he monopolises the miraculous and intercedes with a volatile god.

At the core of his religion is a mystery that only a Hierophant can understand. He trusts his proclamations because they aren’t his to begin with - they belong to a martyred prophet who once swam in molten lava and explained the moon.

The Hierophant gathers his flock from the pasture of gullibility and constructs cathedrals to house their superstitions. The cut of his costume advertises his eminence as the custodian of temples and the broker of salvation. On the expedition towards eternal life, he becomes the connoisseur of karma, propagator of guilt, savant of morality and warden of female fertility.

The Hierophant’s alliances are formed with regimes and autocrats for whom, in the battle for scarce resources, he emboldens the patriot and promotes ethnic cleansing. He sanctifies wars with the instruments of religion, crowns emperors, blesses governments, burns witches, and forms inquisitions in a crusade to eradicate the nonconformist and purge the carnal woman.

At the palace of the priests, the Fool approaches the Hierophant.

“My arrogance is troublesome, and I wish to acquire the humility of a penitent. Can you show me, reverent one, how this can be done?”

Humility of a penitent!” The Hierophant laughs. “What century are you from?”

“I don’t understand.” The Fool replies. “I was told you teach humility.”

“Humility is redundant, and penance is passé in the commodified world.” Explains the Hierophant. “Mindfulness is what you need.”

“Mindfulness?”

“Yes. Mindfulness. Experience the present moment. That is exactly where everyone wants to be. The postmodern person avoids thinking of the past or the impending mass extinction. They consume, compare, and feel superior. They expect happiness.”

“What exactly are your teachings?” The Fool enquires. “Is there a moral aspect to all of this?”

“Morality is integral to the practice of mindfulness, but guilt about the past and fear of the future is no longer encouraged. We’ve moved beyond the Medieval. Heretics are cancelled, rather than burnt. No one gets triggered and everyone feels safe. We promote celebrity rather than sainthood. Look good, feel good, do good. Visible philanthropy is a sacrament.”

“So, what should I seek?”

“Abundance.”

“Abundance?”

“Abundance is where it’s at in this age of personal fulfillment and emotional security. Forget about humility and focus on your unique individual self.”

The Fool follows the Hierophant’s directions and focuses on his thoughts and feelings. He enters a meditative state and visualizes an ideal life as a prosperous celebrity. With all the mindfulness he can muster, the Fool releases his desires into the ether and wills the universe to manifest his vision of abundance.

Time passes and nothing happens. The Fool wonders why the universe is ignoring him.

“It’s a lack of trust on your part.” The Hierophant explains. “Or else your attention is dulled by the dopamine fog of the digital world.”

“I rarely use technology.” The Fool replies. “I will focus on trusting.”

Despite his most passionate attempts to totally trust the universal mind, his vision fails to materialize. He imagines and reimagines until his efforts finally exhaust him and the Fool despairs of being an abundant individual.

“Why doesn’t life work for me?” He demands. “What am I to do.”

“You do not possess the gift of faith.” The Hierophant declares. “Maybe, before you can trust the universe, you need to trust another human being. Ask the Lovers how they trust.”

6. The Lovers

Here is the end of innocence, the apple eaten, the knowledge gained, and the paradise lost. In forsaking Eden, the Lovers’ choice is motivated by the desire for individuality - by a wish to detach from universal consciousness and enter into the world of the human ego.

But this transition into being comes with a price: the awareness of an inner and outer duality. Now, separated from the Higher I, each is a solitary entity at the centre of their own universe, separate from the other and from nature. The Lovers experience a fundamental anxiety as they encounter the reality of survival, aloneness and inevitable death in an alien world.

To escape the isolation and withstand their fear they seek connection. The Lovers reach for each other and discover love.

In the serpent dream of human gratification, a potent appetite arouses every cell when the naked lovers embrace. Each caress is an act of adoration, scent and taste are intoxicating, every glance is a secret shared, the eyes are wells of revelation and the sounds of love ascend with abandon. With their passion confirmed the Lovers reach deeper than touch and into the heart of belonging until, in a surge of delight, their energies flower and momentarily merge into the bliss they had known in the garden.

Within this rapture, each is the other but doesn’t know it.

The Lovers begin in love by falling, not for the other but for the self. The person they fall in love with is strangely familiar because in each other they have found scaffolding on which to screen the anima and animus - their prototype of perfection, the aura of their souls. Thus, the Lovers are enraptured with the perfection of the beloved and while love emboldens the hero and inspires the heroine, everything seems possible.

However, in their brave new world, where nothing can exist without an opposite, the pillars of euphoric certainty cast shadows of anguish and abandonment. With time the infatuation with the “love object” evaporates and when the inner nature of the other becomes apparent the relationship ripens or perishes. The first love becomes a second birth: a mystical marriage for the fortunate or, for the unlucky, a misadventure into a bitter Jerusalem where the jilted lover carries the cross of longing - a longing that will emerge as melancholy in music, haunt the drawn line of beauty, linger in the soul of poetry and resonate with the Fool.

In the way he fears his own fragility the Fool fears love. A life of broken promises and severed boundaries has closed his heart. Intimacy, for the Fool, is a harbinger of hurt and a prospect of further rejection. Only when he is stirred by obsession, disinhibited by addiction or mindless with lust will he risk a relationship – a relationship bereft of empathy and pursued with the duplicity of seduction. The Fool sees sexuality as an instrument of conquest and a sedation of longing, rather than the celebration of a precious bond. The fantasy self he champions slowly poisons all possibility until his replica romance is skinned with resentment and ends in disillusionment.

“Why do my relationships die?” The Fool asks the Lovers.

“You have never known or practiced loving. You act out of an injured pride that can only take and never receive,” the Lovers answer. “You will not know love until you know yourself. And to know yourself you must assimilate the contradictory voices and opposing appetites of your being.”

“And how do I do that?” The Fool demands.

“Seek the Chariot.” The Lovers reply.” “The condition of the Chariot you find will be the condition of the life that you live.”